Marianismo & the Latina College Journey

Photo by Tima Miroshnichenko Edited by Mayra Valle

Growing up in Houston’s Northside within a Mexican Pentecostal church, I learned early on that being good meant being obedient. We were expected to wear skirts, skip the makeup, avoid flashy jewelry, and refrain from asking questions that could deem us “lukewarm Christians of little faith.” It was clear that in order to belong, I had to comply.

While my parents hadn’t gone to college themselves, they still nurtured that dream for me. They knew that pursuing higher education meant access to opportunity. But I felt torn. College rewarded independence and autonomy, while my church praised submission and silence. I didn’t have the language for that tension until I learned about marianismo.

What is Marianismo?

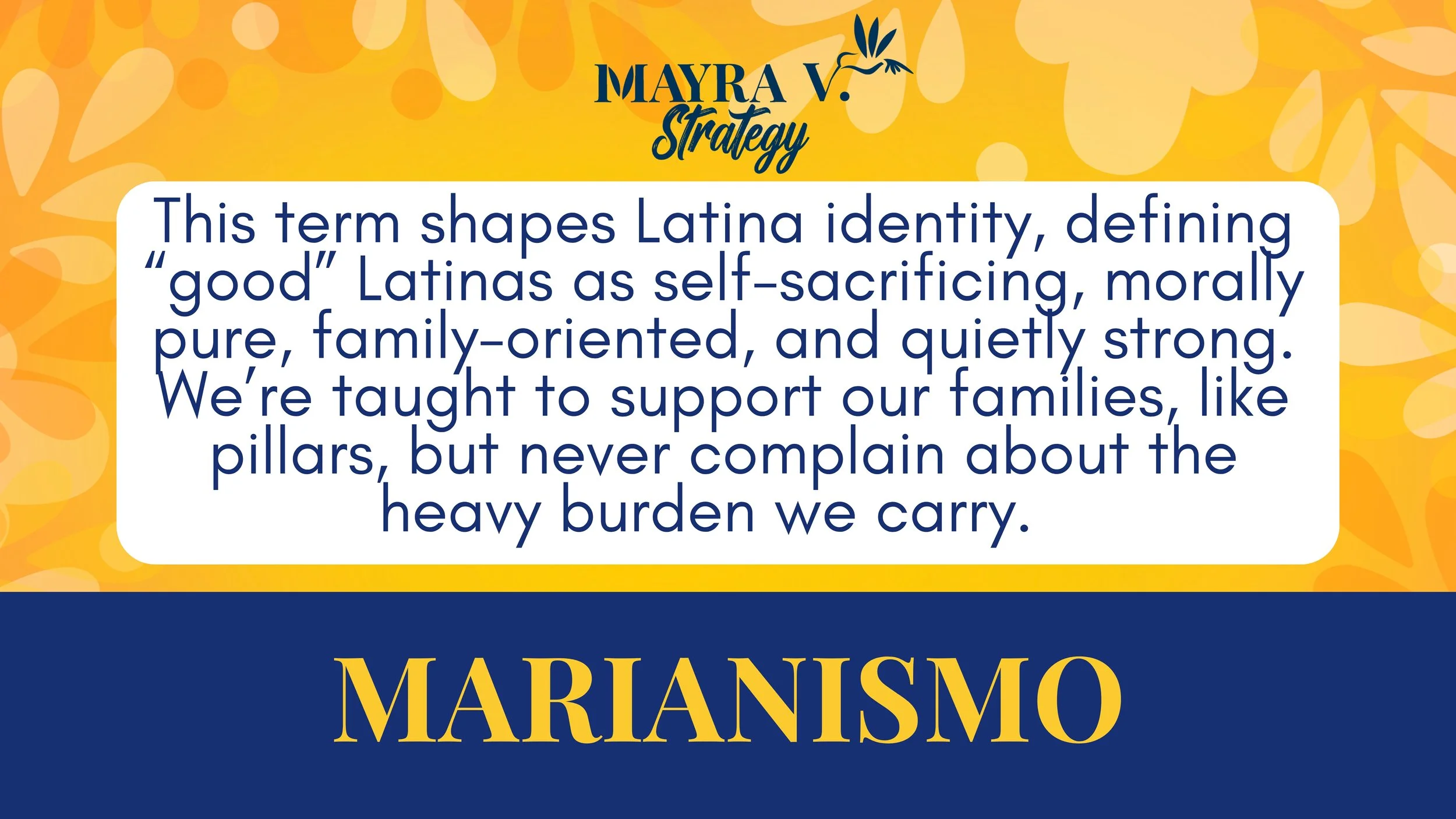

We often hear about machismo, the hypermasculinity centered on strength, dominance and honor. But marianismo, a term coined by sociologist Evelyn Stevens in 1973, is the lesser-known counterpart describing the ideals expected of Latina women.

Rooted in Catholic imagery of the Virgin Mary, marianismo shapes Latina identity, defining “good” Latinas as self-sacrificing, morally pure, service-oriented, and quietly strong. We’re taught to support our families and communities, like pillars, but never complain about the heavy burden we carry.

These cultural expectations taught us that it wasn’t enough to be good. We also had to be palatable. We had to advocate for our communities without being too loud. We had to help others, even if it meant neglecting ourselves. And those expectations don’t disappear when Latinas go to college. Instead, they often deepen.

How Marianismo Follows Latinas to College

Latinas are pursuing higher education in record numbers. In 2023, 23% held a bachelor’s degree or higher, up from 16% in 2013. But behind that progress is an unspoken balancing act, as Latinas seek to honor their family while pursuing an education and independence.

Family First: Higher education is often a shared investment:

55% of Latino college students contribute to family bills, compared to 42% of white students.

Among Latina undergraduates over 25, nearly 50% care for their own children, which is twice the rate of their male peers.

The pressure to “do it all” is real. For many Latinas, success at school also means maintaining important responsibilities at home. From living at home to caring for loved ones to joining the workforce, Latina students do it all, but at what cost?

Silent Mental Health Struggles: This quiet strength slowly chips away at mental health and wellness.

61% of Latina immigrant women report moderate to severe depression or anxiety.

27% of younger Latinas say they feel worried “most or all of the time,” and nearly 1 in 5 experience persistent depression.

Academic studies suggest that affirming positive aspects of marianismo, such as family support and caretaking, can improve Latina persistence in STEM fields.

These aren’t just cultural challenges, they’re systemic. Marianismo often keeps Latinas from asking for support or advocating for themselves in spaces where self-promotion is expected, like in the college admissions process.

Marianismo in the College Admissions Process

Looking back, I see how marianismo shaped my own journey. I was a model student, but under that confident exterior was deep-seeded anxiety. What started as religious anxiety around not being “good enough” evolved into academic insecurity. During college applications, I minimized parts of my story to seem humble and grateful enough for the opportunity.

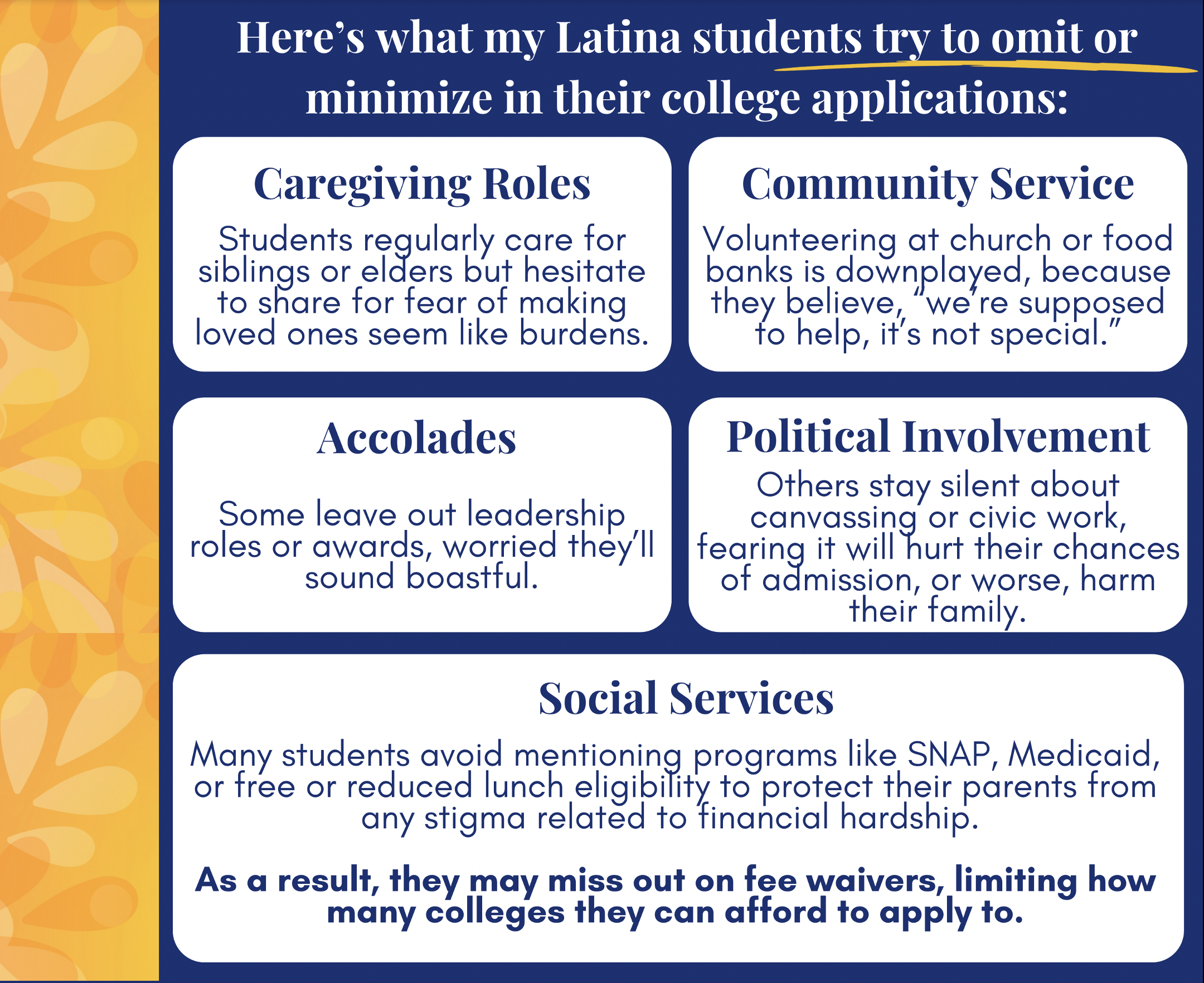

Today, as I work with Latina students navigating admissions, I see the same pattern. They downplay hardships, omit personal triumphs, and hesitate to name their strengths. This silence is protective, shielding them from judgment and protecting their parents from worry. But it also hides their brilliance.

When students make themselves small to fit the mold of marianismo, admissions officers and educators miss out on their full stories.

What Educators and Admissions Officers can do to Advance Equity

Understanding marianismo is key to advancing education equity and supporting Latina students authentically. Here are a few actionable steps:

For Admissions Officers:

Showcase support systems for first-generation, disabled, neurodivergent, and parenting students prominently on school websites.

Encourage recommenders to highlight qualities or achievements students may understate in the college application.

Translate resources, including the Net Price Calculator and financial aid pages, to help families make informed decisions about their student’s future.

For High School Educators:

Avoid deficit-based language when describing first-generation or low-income students, which may include their Latina population.

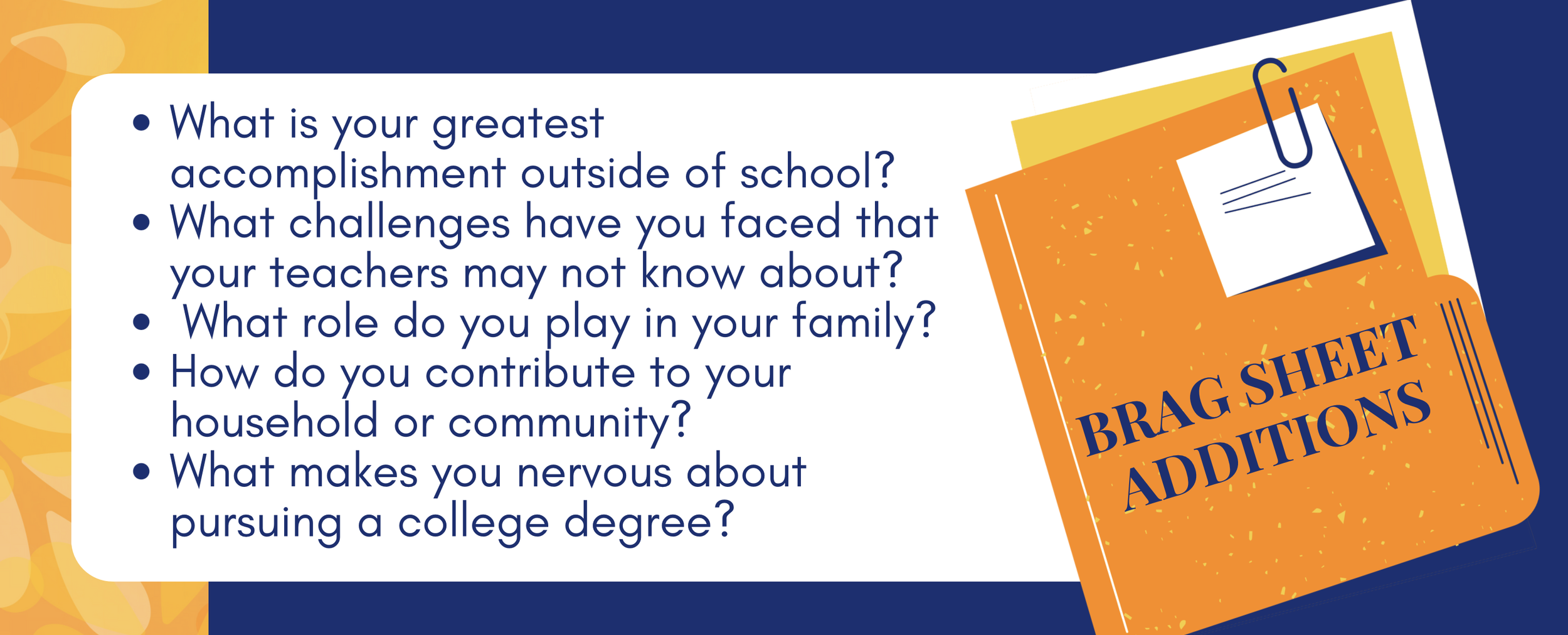

Add reflective prompts to brag sheets or recommendation forms, like:

Demystify the college process, explain fee waivers, application logistics, and scholarship forms in simple and clear ways. Additionally, provide bilingual translation,which could be helpful to students and families.

Host family-friendly events with translators and culturally-relevant examples to foster trust and understanding.

These small shifts can make a profound difference in helping Latina students see themselves as worthy of opportunity, not merely grateful for it.

Returning to My Roots

For years, I thought I had to choose between honoring my faith and claiming my independence through education. Now I know I can have both.

Education doesn’t have to reject culture– it can reflect it. When schools make room for Latinas’ quiet resilience, family-oriented service, hidden labor, the sacred collective care, they don’t just empower individual students. They transform systems that once asked them to shrink.

For too long, marianismo has taught Latinas to be strong in silence. It’s time we honor that strength out loud, so every Latina student knows that her complex story, her faith, and her future belong in the same breath.

Further Reading

Latino Students and the Educational Pipeline — Educational Policy Institute (2005)

Ryan et al. (2021). Stress, Social Support and Depression Among Latina Immigrant Women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research

Bocchi, Mary. Marianismo. Lewis & Clark College.

Sánchez et al. (2018). Examining Marianismo and Mental Health in Mexican American Girls. PubMed Central

Milian et al. (2025). Marianismo, Mental Health, and Education Persistence of Latina STEM Students. International Journal of Progressive Education Studies

Frederick et al. (2022). Your Family is Always With You: Parental Relationships Among Latinx Students Pursuing STEM Careers. CBE—Life Sciences Education